…to misquote Mark Twain. But as the housing pandemic continues, even beyond a point that we’ve become accustomed to and incidentally, with a prospective Labour government offering no answers, it’s essential to challenge a lie that is in danger of taking hold in collective consciousness. “There aren’t enough homes because there are too many people”.

It’s a seductive proposition. The population is increasing and new homes aren’t keeping pace, ergo, if there are fewer people, there will be more available homes. I’ve recently had the experience of marking undergraduate papers about causes of the housing crisis and about a quarter of them attributed population growth and immigration as the main factors. Interestingly, this is not something I’ve ever taught and I’d guess that about half of those making the argument are themselves immigrants. I’m pleased they’re thinking for themselves, but worried how this crude argument is being internalised, particularly because it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), there were 24,782,800 households in England and Wales on Census Day 2021. On the same date, according to the ONS, there were 26,394,777 dwellings in England and Wales. So, the number of homes exceeded the number of households by 1,611,977.

Anyone wanting to attribute the housing crisis to population or immigration needs to look elsewhere.

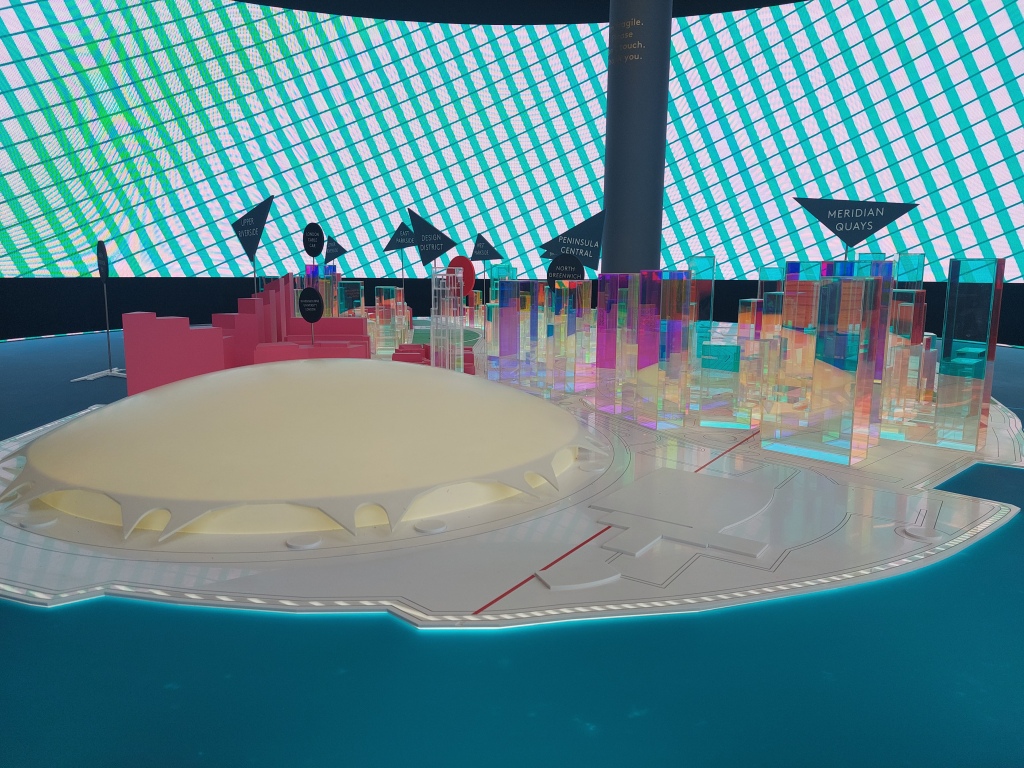

As Professor Danny Dorling has been arguing for years, the housing problem is primarily one of distribution, not supply. Also drawing on 2021 Census data, the ONS points out there were 1.6 million empty homes in England and Wales. There could be a variety of reasons for this, but the ONS estimates 12% of empty homes are second homes. The BBC reports that the number of short-let holiday homes has risen by 40% in the last three years.

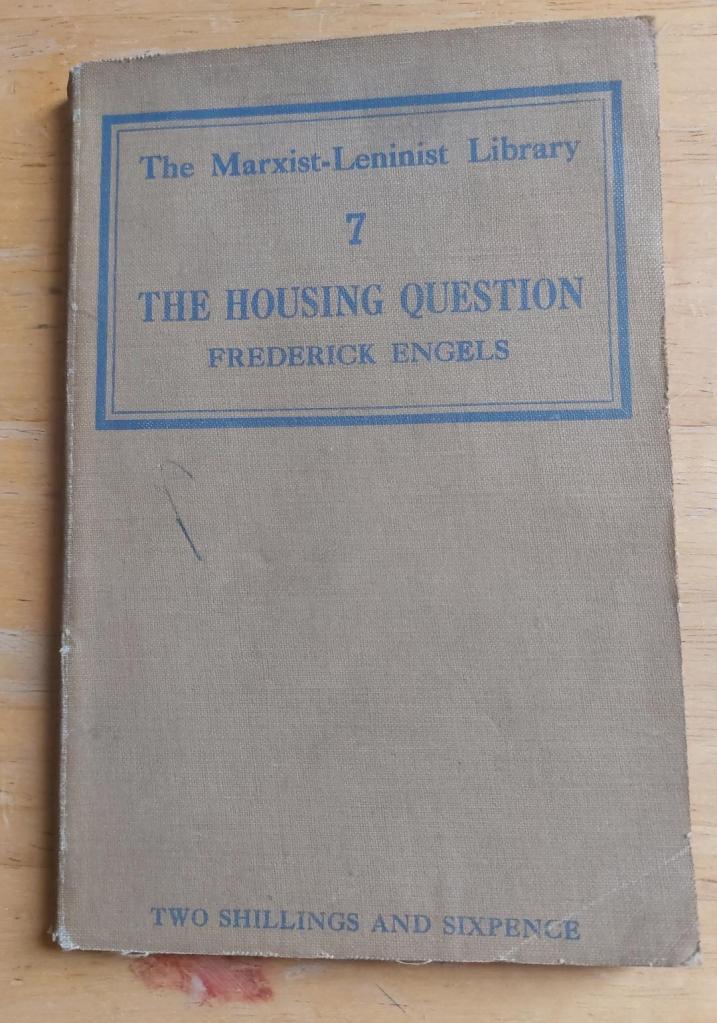

As most of my students have grasped, almost every element of UK housing policy for the last 40 years has encouraged the use of housing as a form of financial speculation and it has created a complex web of vested and conflicted interests that is very difficult to unpick. Instead of addressing these issues, it is much easier to look at population growth and immigration, precisely the scapegoating strategy of the current government, its Labour shadow and the Farragists

There’s nothing new about this phenomenon. I’m reading a lot about the Jewish left in early 20th Century New York City at the moment. From building a genuinely radical, at times revolutionary, alternative to the brutality of emergent industrial capitalism, by the 1920s, some leading trade unionists and socialists were retrenching towards a “no more immigration” policy. In part, they were responding to the pressure from members and constituents living in over-crowded, over-priced, privately-rented slum housing, seeing more people arriving on the same boats they had got off themselves only a few years earlier. (By the way, most of these people would be classified as “illegal” today, arriving as they usually did without legal documents and with the assistance of “traffickers”.)

The full folly of this pandering to reactionary, divisive sentiment was brutally exposed soon afterwards, when an enfeebled left tried to respond to the rise of fascism. We’re not there yet. But allowing false arguments about housing shortage to circulate freely is a vital weapon of mass distraction in the hands of the profiteers and racists.

You must be logged in to post a comment.